5 Most Popular Brain Myths

Fake news has become a hot topic. But the deliberate disinformation of the public through traditional or social media goes beyond news: there is also an alarming rise in "pseudoscience." The brain and mind feel extremely familiar to us. We spend a lot of time in our own heads. That's why it's so easy to spread false—but nice-sounding—information about the brain.

A neuromyth is a misconception about how the brain works that is held by a large number of people.

5 popular misconceptions about the brain that are actually neuromyths

Neuroscience is quite young—neuroimaging technologies have only been developed over the last twenty years. As a result, it is a constantly evolving field, and it is quite difficult to separate fact from fiction. Here are some of the most common neuromyths, how they originated, and why they are incorrect.

Myth 1: We only use 10% of our brain

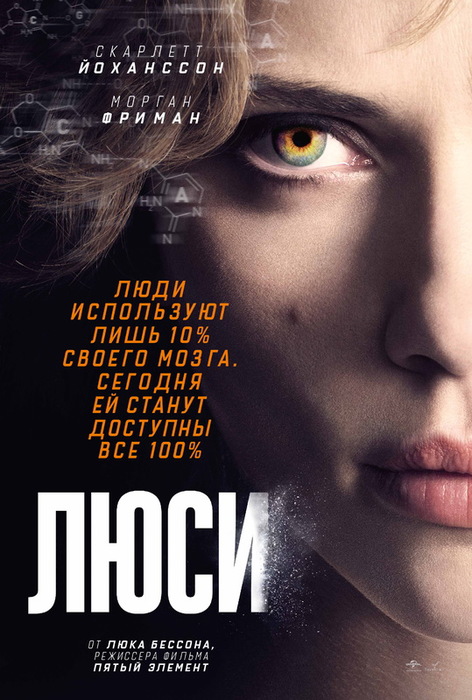

This neuromyth was the basis for at least two science fiction films: "Limitless" by Neil Burger starring Bradley Cooper and "Lucy" by Luc Besson starring Scarlett Johansson.

People like this myth because it makes them feel good. It implies that you may have a huge untapped potential that can be unlocked with the right techniques or tools. Marketers also love this myth because it helps them sell dubious products that supposedly allow access to the remaining 90% of the brain's capacity.

Why it's wrong: There is a wealth of evidence showing that no matter what a person is doing—even if they are told to simply lie in a scanner and do nothing—almost all areas of the brain are active. Secondly, from an evolutionary perspective, it makes no sense to have an organ that is 90% unused. Especially when it comes to the brain, which consumes a staggering 20% of the body's energy despite making up only 2% of its weight.

Myth 2: We are either right-brained or left-brained

Every day, companies pay for seminars that teach their employees that they are either right-brained (artistic expression and creativity) or left-brained (logical thinking and calculation).

Why it's wrong: Neuroimaging studies show that both parts of the brain are active when people engage in creative tasks. There is absolutely no reason to think that certain forms of thought—say, creative versus rational thinking—are localized in a particular hemisphere of the brain.

Myth 3: We have multiple intelligences

Harvard psychologist Howard Gardner proposed the theory of multiple intelligences in the 1980s—and I say "proposed" because there was no real data in this theory: it was just Gardner's opinion that there are multiple intelligences with different levels in people.

He started with a list of seven "intelligences": musical-rhythmic, visual-spatial, verbal-linguistic, logical-mathematical, bodily-kinesthetic, interpersonal, and intrapersonal. But since that was not enough, he added a few more (still without any data to support his claims): naturalistic, existential, and moral intelligence.

Why it's wrong: First, what Gardner calls intelligence can simply be called skills. Second, research shows that our skills are not widely independent of each other. People who tend to do well on one type of test tend to do well on all of them. This is called "general intelligence," and it has much more tangible evidence to support it than the theory of multiple intelligences.

Myth 4: IQ tests just tell you how well you take IQ tests

This was one of the most surprising for me because I truly believed this neuromyth before writing this article. Although IQ tests certainly have flaws in all respects, they are some of the most reliable and predictive tests that exist in all of psychological science.

Why it's wrong: A study of nearly a million men who took an IQ test as part of their military service in Sweden showed that the higher the IQ, the longer they lived. Many studies have shown that IQ tests do predict mortality, as well as educational achievement, job success, physical and mental health, and many other things.

Myth 5: People have different learning styles

The theory of learning styles states that people differ in how they learn, which is due to some innate property of their brain, and that teaching should be tailored to their specific learning style. According to this theory, some people have a more visual learning style, others auditory, etc.

Why it's wrong: Research shows that changing the teaching method does not affect student success based on their preferred learning style. In short, we do have a preferred learning style—one that feels more comfortable—but using another does not affect our performance. We do not have different learning styles; we just have different learning preferences.

The Problem of Spreading Neuromyths

There are many other neuromyths. But what is surprising is that they are believed not only by the general public.

Alarming statistics: Studies show that 59% of the general public, 55% of educators, and 43% of people with a high level of neuroscience knowledge believe in the "Mozart effect"—a theory that suggests listening to classical music can increase our intelligence. Which is false.

Even more depressing is that 14% of people with a high level of neuroscience knowledge believe that we only use 10% of our brain. Overall, the study found that on average, 46% of the most educated people in the field of brain science believed in these neuromyths.

Worst of all, research shows that more education may not fix this. Taking a course in educational psychology improves general neuroscience knowledge but does not reduce belief in neuromyths. Neuromyths seem to be really sticky. They feed our desire to believe that everyone can be good at something, that we have untapped potential, that we are unique.

Conclusion

Although it has been shown to be incredibly difficult to change people's minds when it comes to neuromyths, I hope this article will be a small contribution that can enlighten people who are willing to let go of some firmly held beliefs about how their brain works.

Understanding how our brain actually works does not make us less special or less capable. On the contrary, it helps us to better use our real abilities and avoid false promises.

Critical thinking and scientific literacy are our best tools against disinformation.